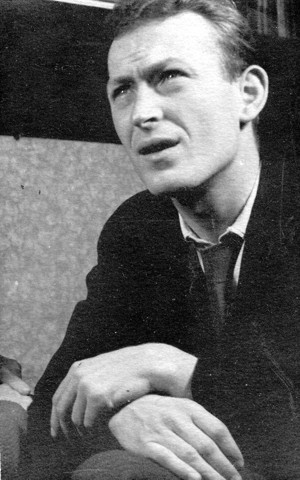

Franςois Sammer |

Franςois and Agnes Sammer |

Golconde Architects

Antoinin Raymond

Franςois Sammer

George Nakashima

Franςois Sammer

In about 1936 we met a delightful person who had come out of the Czechoslovak Siberian Army, a young and handsome Czech architect, Franςois (Frantichek) Sammer. He was a pupil of Le Corbusier and went with him to Russia and then joined the Siberian Army, which eventually took him to Shanghai and to my office in Tokyo. He was one of those totally dedicated youngsters and was an ideal companion on the design of Pondicherry.

Antonin Raymond

Sammer was a student of Le Corbusier, and was part of the team that went with him to Moscow in 1933 to work on a vast housing-project there. He and his wife, Agnes, had met in 1931 in Paris where she was studying sculpture. He was Czech, she was born in Honolulu, of Norwegian parents. They had gone to Russia together and married there-which in Russia was as easy as going to a hotel to book a room: no church-going or other formalities were involved, except signing a register. In those days they were both convinced atheists; it was a fashion among the younger generation in those days, mainly because they confused God with the Church; they were very much against the Church for they saw how it exploited the ignorant masses

Mrityunjoy

François Sammer, a pupil of Le Corbusier, a Czech like myself, worked in 1937 in my office in Tokyo and naturally influenced my design in Japan, which in turn influenced the young Japanese architects before the war. Sammer was working with me in particular on the Ashram for Sri Aurobindo Ghose in Pondicherry, India. This was widely publicised in Japan and was a great inspiration to the young Japanese architects.

Antonin Raymond

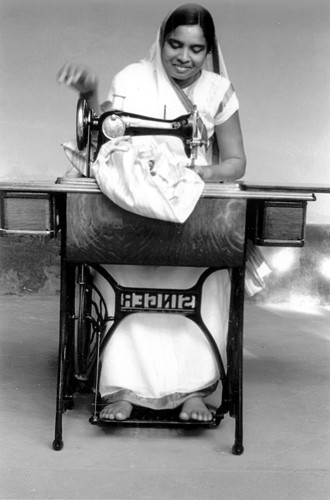

François settled in Tokyo, but he was chosen by Raymond along with George Nakashima, an American Japanese, to go to Pondicherry in India to build Golconde. So Agnes received a letter from Franςois not to come to Tokyo, but to meet him in Pondicherry (address c/o Mr. Sri Aurobindo Ashram) as they knew nothing of the word yoga. So Agnes arrived early in 1938 by ship, which brought her directly to Pondicherry. François and Raymond were already here and Nakashima. She was quickly accepted in the Ashram family – no tea party but all action. Mother put her to work – to prepare trousers, shorts and shirts for Golconde workers.

Mrityunjoy

Sammer accompanied us on our trip to Pondicherry and worked devotedly in the Ashram. I left him with Nakashima in India, and soon afterwards the Second World War separated us. I heard nothing of him until August 1966, when I heard from him in Czechoslovakia, where he was practising architecture.

Antonin Raymond

The Mother put Agnes to work preparing trousers, shorts and shirts for the Golconde workers. She remembers Franςois telling her of the Mother's advice: "Don't consider the amount of money or the length of time: I want a good building." It was the first time in his life he had heard this from a client.

Mrityunjoy

Pushpa Patel. Albert & Ashok's mother |

Sammer at work |

|

|

|

|

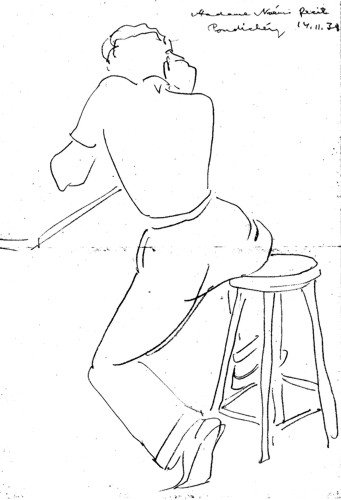

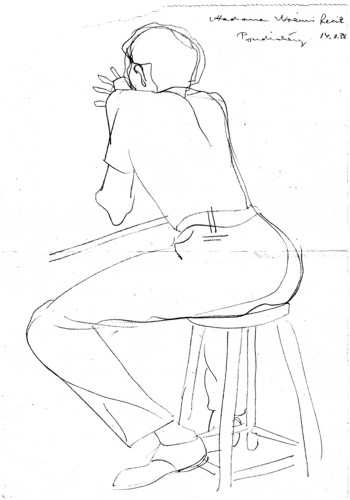

| Sketches of Sammer by Raymond's wife, Noémi. Pondicherry, 14 Nov 1938 | ||

One memorable scene of tragic-comedy between a coolie and Sammer comes to mind. Sammer saw a labourer approaching him from a distance; he did not want to deal with the coolie, so he shouted, “Va-t’en!” which in French means, “Go away!” but the coolie kept coming. The closer the man came, the more annoyed Sammer grew, and he kept on shouting “Va-t’en!” unfortunately in Tamil “Va”means “Come” — just the opposite of “Go”. Terrified, the man crept towards Sammer, who was on the point of losing his temper. Chandulal, our engineer, was with Sammer and he understood the joke; keeping his gravity before the worker, he patted his neck and told him to go. The man went away bewildered. Then Chandulal burst out laughing and explained the misunderstanding to Sammer.

Mrityunjoy

I did the furniture for the miniature Golconde, but Sammer did it for the building after I left Pondicherry.

Sundarananda

One picture of Sammer remains unforgettable to me, it is his first approach to the Mother in the open pranam hall, just in front of Amrita’s room. Since November 1931, the Mother had been sitting there each morning to receive pranam from the sadhaks and to give them flowers and her blessings. Sammer had already been in the Ashram for some months by then. Suddenly that day he stepped inside the hall and knelt down in front of the Mother, seated in her chair. She looked at him with her smile that melts stones, and he looked back at her with the innocent curiosity of a child. His unexpected entrance and the sweet reception given him by the Mother changed the whole atmosphere for a moment. He bowed down towards her lap, she pressed his head gently and patted it for some moments; then he got up, received a flower from her hand and she bade him goodbye by a sign of her head. He went out, but not right outside: he stepped towards Nolini’s room, to the hall where the big clock stands now. He avoided the people looking at him, but we could see he was wiping his eyes with his handkerchief. Evidently there was an overflow of emotion he could not control.

Mrityunjoy

After that Sammer remained with us in the Ashram for four years, working with us on Golconde, although his work was more in the office making drawings and calculations. We did not see him frequently, as we saw Nakashima, on the concreting site before the form-works were laid. He rather came when the actual concrete laying was being done.

Mrityunjoy

Here are two outstanding examples of this approach. Normally, in reinforced concrete work where large areas are cast in form work, when the form work is removed, the faces of the cast areas are plastered over and made level and smooth. But for this work at Golconde, François insisted that the surfaces be left as they were, after the form work was removed and only smoothed over with a carborundam stone. In this way, the quality of the work could be seen and so the work had to be done very carefully, there should be no holes no blank spaces and this was done by having the concrete vibrated at the time of casting. This was quite a new technique to us. The details of the form work could be seen, the joints of the planks, the screw heads and even the grain of the wooden planks. All this was part of the aesthetic detail in the architecture and those who visit Golconde are impressed by it. The other example was in the use of the wooden planks for the staircase hand-rails. François insisted that they planks should be left with all the defects in them, defects which all planks have and which are normally covered over. These small defects add to the beauty of the wood and show its intrinsic value.

Udar

The Service Tree which we had planted began to grow and the branches spread onto the roof of the old kitchen. When we had to remove the old kitchen, what to do with the branches which were taking support on it, how to support them? So a scaffolding was designed. We call it the “Sanchi pillars.” The whole construction in the Ashram courtyard was done by Sammer. At the foot of each pillar you will find a square place, the Mother’s idea was to have grass in each square, but as that could not be done, pebbles were put.

Dyuman

Sammer designed the concrete pillar-supports for the Service tree in the Ashram courtyard. The Mother liked them very much. But in those days there was no question of having a Samadhi at that spot. The Mother had a young Service tree planted there in 1931, long before the architects came, and she had carefully protected it against injuries through the years, as a mother protects her growing child.

Mrityunjoy

In 1942 Sammer joined the British army as a volunteer, wishing to do whatever he could to help his country, which by that time had been entirely occupied by the Germans. Later we heard that Sammer had been posted in Burma as a Captain in the Royal Engineers, and there was a rumour that he had been injured and flown to England for urgent treatment.

Mrityunjoy

Then, twenty-five years later, in the summer of 1968, Pavitra surprised me with the sweet news that not only was Sammer alive in his native land of Czechoslovakia, but he had heard about Auroville on the radio and television and read about it in the papers and was very interested.

Mrityunjoy

Letter to Agnes from Sammer dated October 1972 (he died on 17 October 1973)

My dear Agnes,

I have been much occupied the whole month but had quite a good time. Reading, writing, deliberating, as proper to an aging welter-weight amateur – even sketching houses – also dreaming, which is part of the profession and takes much time, as you know.

Franςois

Agnes was lucky enough to see the Mother and receive Her approval to come back and settle in the Ashram. She told us that since she left the Ashram in 1939, she had seen the violence of the War and had passed through a series of wars in her own life, but had never lost contact with the Mother; she realised that not only was her return to Pondicherry destined, but her going away was also necessary for the evolution of her soul. We were happy to hear this from her.

Mrityunjoy

It is pleasant to remember Sammer, he was to us never a foreigner, a Czechoslovakian, but a friend and a brother, an eternal child of the Mother.

Mrityunjoy

Raymond

I was born on the 10th of May, 1888, to Alois and Ruzena Rajman, both of Czech peasant stock. The transformation of my family name from Rajman to Raymond owes to developments long after-wards, when I had left Bohemia and was living in the United States.

Antonin Raymond

Raymond on his toy horse, 1890 Kladno |

Raymond’s Parents – 1890 |

|

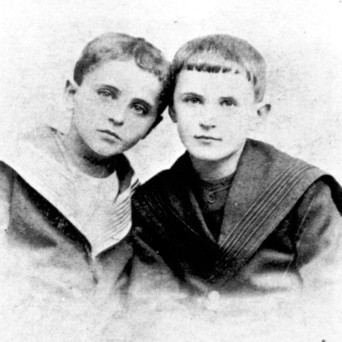

With his brother Frank (left) – 1894 |

Self – portrait - 1908 |

Born in 1888 in Kladno, Bohemia, Raymond’s parents were Czech, of peasant stock, and they lived in a comfortable upper middle class home with their six children, of whom Antonin was the third. His intense imagination, which sometimes astonished other members of his family, found encouragement and direction under the influence of an extraordinary primary school teacher who imbued his pupils with a love of the arts, teaching music, singing, drawing and painting in addition to classical academic subjects. The discipline and joy of artistic accomplishment has never left him and to this day he continued to play the cello, paint, do sculpture and make pottery for all of his life.

Antonin Raymond

I lost my mother in my tenth year and the tenderness I felt for her lived on in my love for my maternal grandparents and the long periods of time I spent on their farm.

Antonin Raymond

At this early time I already knew that I was going to be an architect, and if anyone asked me my name, I would reply quite proudly, “Antonin Rajman, Architect.” I wasn’t altogether sure what it meant, but I did know it had something to do with making houses. In addition to making drawings of little houses, I invented all kinds of guns that actually worked. It was not all pure imagination. I must have discovered Jules Verne when I was about six years old, and his stories provided me with a powerful stimulant.

I built houses, in fact whole villages, of paper and paste, coloured them with water-colours and put coloured gelatine into the windows; at night I put tiny candles inside the houses and sat for hours admiring the scene. I enjoyed great peace and contentment doing this. That is perhaps why I became a real architect. During my years as a student, I had to work amazingly hard at subjects not at all to my liking. Even now I it find it a struggle. But I love architecture and all that attends it, painting, sculpture and music.

Antonin Raymond

For a year after his graduation he worked briefly with a Yugoslav civil engineer in Trieste and then took a freighter for the United States, arriving in New York City in 1910 with 30 dollars in his pocket. Sometime in September 1910, I succeeded in getting a job on a small Italian freighter as an assistant clerical and mechanical mate and off I was for New York.

Antonin Raymond

He went to see the manager of Cass Gilbert’s office, an American-born Czech, and was immediately put to work. But in his enthusiasm, naiveté and pride, he agreed to work without salary until Mr. Gilbert should return from Scotland where he was grouse-shooting. The 30 dollars didn’t last long. For three months he lived on 92nd Street where he had a room and breakfast for one dollar a week. Every day he walked to the office on 24th Street and back again, without lunch and then washed dishes in a 25c dinner restaurant for a meal. It was a grim beginning indeed for one who had come to the promised land with such lofty visions.

Antonin Raymond

Every day I walked from 92nd to 24th Street, worked all day, had no lunch and walked back to 92nd. There I washed dishes in a 25 cent dinner restaurant. The reward for which was a meal of what ever was left. At noon I sat on a bench in Madison Square Park watching the squirrels eating peanuts people gave them. Once I spotted a dime near a peanut; I got it and ran to a lunch wagon. I bought a bottle of milk and a loaf of bread. It was a feast.

By the time Gilbert returned from Europe I was pretty well a wreck physically. Starvation, daily long walks and serious work in the office exhausted me. I must have looked sick for he sent me to a farm to recuperate.

Antonin Raymond

On Mr. Gilbert’s return Raymond was given seven dollars a week for salary. This enabled him to move to a place on East 24thStreet where he lived with three other architectural draughtsmen and paid a dollar a day for room and board. In the office he designed exterior details, Gothic in character, for the Woolworth building.

He began studying painting at the Independent School of Art in the Lincoln Square Arcade Building in 1912, but was forced to curtail a painting trip to Italy and North Africa with the onset of World War I.

Antonin Raymond

Raymond occasionally did renderings for other architects and on one such job early in 1914 he made $1,000. Immediately he took leave from the Gilbert office and went to Italy where he rented an atelier north of Rome and painted feverishly and happily for several months.

Antonin Raymond

War broke out that September and it was imperative that he return to the United States. On the dock in Naples he met Noémi Pernessin. Later he showed her some of his more avant-garde paintings and to his delight she responded with understanding. She herself was a designer and illustrator and did an animal cartoon strip for an American newspaper under the name of Nip. They were married on December 15, 1914. They worked as partners in design for over sixty years.

Antonin Raymond

The United States had joined the Allies and Raymond, with his European background and knowledge of languages, found himself in the Army as a member of the US intelligence corps. He served on the French and Italian fronts, and in Switzerland as liaison officer.

In 1915 he and Mrs. Raymond went to Spring Green, Wisconsin to join Frank Lloyd Wright at his establishment in Taliesin. The experience of learning to know this most creative and courageous personality in his own surrounding is considered by Raymond to be one of the most remarkable happenings of his life.

Antonin Raymond and his wife Noémi had spent time with Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin in 1916 and in 1920 Wright had invited Raymond to come to Tokyo to help complete work on the Imperial Hotel. When the hotel was finished, Raymond decided to stay in the city and establish an architectural practice there.

Antonin Raymond

The changing of the seasons, the beauty of the countryside, the earthy and practical activities of farm life, quickened in him an everlasting love of and respect for nature. Both Noémi and I had been brought up in a European spiritual and intellectual milieu, she in France, I in Bohemia. We both felt intensely the pains of existence in surroundings lacking all that had contributed to our happiness in the old world.

In a Raymond house, there was no harsh separation between nature and man, but a fluid relationship which varied with the weather and season. According to Raymond’s method of design, material must be subservient to an idea, and the building of a shelter is the exteriorisation of this idea.

Antonin Raymond

This spiritual concern for human life that Raymond has developed in his long career in the artistic and cultural atmosphere of Japan is the great quality which distinguishes him from the leading architects in the materialistic atmosphere of the Western world.

His search for purity in form comes from this awareness of the powers of nature. He feels that science and technology have produced a miasma of materialism in the West which has all but destroyed true creativity in the arts because it has all but destroyed the spiritual quality of life.

There is a difference in the way things are seen in the East and in the West. Raymond points out that there is a difference in the source of inspiration between the Eastern and Western craftsman and artist. He says: The Japanese genius is not intellectual like the French and not practical as the American. It is intuitive and therefore sometimes reaches more deeply into the universe of truth than the logical mind of the westerners.

Antonin Raymond

We found Pondicherry to be an extremely interesting and in many ways charming city. The architecture is colonial French from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, well laid out streets, squares and fine public buildings. There was a library, the shelves of which were stacked with original volumes published in the 1600s and 1700s, and much of the original furniture and equipment was intact.

The cities of India are not clean, and certain of the customs of the people of the Pondicherry populace were puzzling. One did not dare to walk on the public beaches for fear of the filth with which they were littered. Yet, the Ashram of Sri Aurobindo, quite a portion of the town, was immaculate, better kept in fact, than any place I have ever visited. The many buildings were kept in perfect condition. The narrow streets of rose-orange sand, carefully swept, stand out in a surprising contrast to the rest of the city. On such a road we were given a house, a regular palace on the seashore with a terrace overlooking the harbour, and servant quarters for a couple of servants who were graciously anxious to take care of all our needs. The food at the Ashram was strictly vegetarian; even tea and coffee were not on the menu. We decided to live like the disciples, and it was a most amazing experience.

Antonin Raymond

A daily ritual was the hour of meditation attended by most of the disciples of the Ashram. I was not required to attend but I often did because the setting was an open hall between two beautiful gardens and I found this time spent in trying to detach one’s mind from all earthly concerns a great relaxation. The Mother presided over these sessions, standing in meditation on a balcony above us. The hour of meditation over, the disciples quietly departed in the golden after-light, walking along the orange-coloured sandy paths amid the flowers and beneath the bluest sky that ever was, in their flowing robes of white and yellow. Every cast of features, all shades of complexion were represented

Our 8 months at the Ashram were extremely fruitful and instructive. Not only was the life in this Indian monastery the revelation of another way of life but the conditions under which the work of the building was done were so remarkable when compared to those we had known in this materially bewildered world, that we lived as in a dream. No time, no money, were stipulated in the contract. There was no contract. Here indeed was an ideal state of existence in which the purpose of all activity was clearly a spiritual one.

Antonin Raymond

At times it was almost unbearable to us to him reject what the Mother suggested about some way of doing something connected with the Golconde . , say that the Mother was right, it should be like that.

Mrityunjoy

In spite of the heavy work to get the building designed and built, we could not resist the temptation to do a lot of sketching and painting in both town and country. Southern India is so suffused with colour that to my mind it offered ideal conditions for painting and was an endless source of inspiration.

As for their food and drink they were as much European as anyone, and the Mother instructed us to provide what they asked for. Even in February, when we feel cool here, they were feeling hot, so we had to arrange to send them to Kodaikanal, a nearby hill station. They spent about three weeks in the bungalow of a person we knew there. When they came back, I was surprised to see the volume of paintings and sketches each had done during their tour.

Mrityunjoy

A very amusing experience came our way just before the real summer heat started in May, and that was an excursion to the state of Mysore to enjoy a trip on elephants in the jungle. We were invited to this party by a high government official of the state, (probably Sir Akbar Hydari) who also was greatly responsible for furnishing the money necessary to build the dormitories at the Ashram.

Antonin Raymond

Raymond sought to mitigate the effects of the Pondicherry climate and orientated the Golconde dormitory (as it became known), so that its main façades faced north and south to make use of the prevailing breeze. A combination of moveable louvers on the exterior skin and woven teak sliding doors permitted ventilation without compromising on privacy. The building is still in use as an Ashram dromitory today.

Antonin Raymond

Noémi’s influence on Raymond during the inter-war years was substantial. She encouraged him to break away from Wright’s rigid style and explore the design of the Reinanzaka House. She increased her interest in Japanese art and philosophy, including ukiyo-e woodblock prints and introduced Raymond to various influential people, including the mystic philosopher Rudolf Steiner. She expanded her design repertoire to include textiles, rugs, furniture, glass and silverware. Noémi exhibited in Tokyo in 1936 and New York in 1940, and her textiles were chosen by American designers like Louis Kahn to cover furniture in their designs.

After having been used to the completely vegetarian diet at the Ashram, the very smell of the steamer and of cooking nauseated us, and it was very difficult for us to eat anything for some time. It was quite remarkable how the vegetable diet, the lack of alcoholic stimulants and tobacco refines one’s capacity to taste and enriches one’s ability to truly enjoy what Nature meant to give us as nourishment. In about 1934 or ’35 George Nakashima joined our office and worked for me till about 1939. In 1938 I took him with me to India to work on the Sri Aurobindo Ghose dormitory. I left him there to finish the supervision. I did not hear from him till 1941, when I had a communication from the Dean of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, informing me that Nakashima, who was a graduate of M.I.T., was interned together with his wife and children in a desert camp in Utah, and asking me to try to get him out of there and do what I could for him.

Antonin Raymond

The Raymonds also used these connections to bring new life to the role of the architect as a master-builder―where simplicity and truth were found in the beauty of natural materials and in craft of fine workmanship. Dissatisfied with the dehumanizing effects of industrialization that they saw in much of the architecture of their day, the Raymonds sought to reinvest architecture with “an atmosphere of calm and serenity, life and joy.” In so doing they brought about an architecture of quiet elegance which drew from the principles of the past as well as the technologies of the present to create a way of living for the modern world.

Antonin Raymond

A Japanese farm at the time of my arrival in Japan forty years ago was a marvel of integration, complete and perhaps not to be found anywhere else in the world. It grew out of the ground like a mushroom or a tree natural and true, it developed from the inside function absolutely honestly, all structural members were expressed positively on the outside, the structure itself was the finish and the only ornament, all materials were natural, selected and worked by true artist artisans, everything in it and around it was simple, direct, functional, economical.

The people, their dress, their utensils, their pottery, paintings, gardens, all expressed a marvellous unity of purpose clearly developed through ages by a natural process like anything else in Nature. It clearly showed to me an unparalleled love of Nature with a capital ‘N’ and a Divine guidance. Ever since then, I tried to learn from it, grateful for its existence and realising that it contained absolute principles… the simplest, the most natural, the truly functional, the most direct, and the most economicalonly, is truly divinely beautiful. To attain that one must design from inside out, … not from outside in.

Antonin Raymond

On the oneness of life and creative work, Raymond wrote in 1958:

I believe that life philosophy and design philosophy are one thing, and if the fundamental precepts of life’s philosophy become confused so will the design in any field of art become confused.

Antonin Raymond

Nakashima

George Katsutoshi Nakashima was born in 1905 in Spokane, WA. Trained as an architect at the University of Washington and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he first began furniture-making ventures in India, Japan and Seattle, WA. Through the sponsorship of Antonin Raymond, he was released from the internment camps in the Idaho desert and founded his workshop in Bucks County about 1945.

Mira Nakashima

In his 1981 book, The Soul of a Tree, George wrote that in his youth he often “roamed the mountains of the Pacific Northwest alone, in search of a reason for being” and embarked on “a strange unending search for an inner peace which I strongly suspect did not exist”. His toughness and rugged endurance was engendered by a family that clung stubbornly to the virtues of hard work and moral idealism.

Sundarananda

In 1929. the year he graduated from the University of Washington, he was awarded a scholarship to the Harvard Graduate School of Design. For the next two years, Nakashima worked as a mural painter and designer for the Long Island State Park Commission.

Sundarananda

At the University of Washington he began to study forestry, but switched to architecture after two years. He was not an especially good student overall – he recalled that he failed French three times – but he was an outstanding architecture student. He had an intrinsic artistic mastery of line and form manifested in pen and ink architectural drawings, and as a result was awarded a scholarship for a year of study at the Ecole Americaine des Beaux-Arts in Fontainebleau, France.

Sundarananda

In Paris, George found a room in the district of Montparnasse. He divided his money into two parts per month ($8 for rent and the rest for food) and often went hungry. He became friends with a Russian emigré Ivan Wyschniegradsky, an avant-garde composer through whom he was able to earn a modest living drawing music staves on paper, which he did with the steady hand of an architect.

Sundarananda

Two works of architecture that he saw while in France had a profound influence on Nakashima’s life and work. The first of these was the cathedral of Chartres.

His mystical appreciation for the cathedral was deep and unending. The church seemed to him a manifestation of a deep yearning of the human spirit.

What impressed him the most was the manner in which the cathedral was conceived and built, constructed by a community of faith.

Sundarananda

The second building that profoundly influenced Nakashima’s thinking was Le Corbusier’s Pavilion Suisse, which was being constructed near his room in Montparnasse.

Le Corbusier believed that the plan of a house should be free-form and open, with walls that shaped the interior but did not close it off, nor inhibit the spatial continuity throughout. He liked simple, clean lines and favoured horizontal courses of windows to admit as much light as possible. He calibrated his proportions on a module based on the height of a man, which, he believed, assured a sense of harmony throughout the work and promoted a feeling of peace and well-being.

Sundarananda

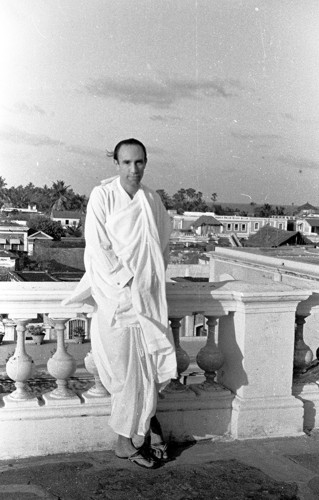

I arrived at the Ashram quite early in the morning. Here I was received warmly by the Mother and members of the Ashram. It was not long before I slipped into the routine of the simple life led there. I made friends almost immediately, joined them at meals, participated in the few set occasions, like evening meditations, and began my task of designing and constructing the Ashram’s major building.

Sundarananda

This was some ten years after the Ashram community had been organised. When I arrived, there were about two hundred men and women from all over the world living there. The monklike life was beautiful and unadorned. The day had not yet come when the Ashram would have a more direct relationship with the outside world. Since I felt I was receiving more than I was able to give – the answer to all my searches, finally conferring meaning on my life – I refused a salary and joined the community. Sri Aurobindo gave me the name of Sundarananda, which translates from Sanskrit into English as “One who delights in beauty”, the suffix –ananda meaning “delight”.

Sundarananda

The Ashram was not an institutionalised religious organisation, actually not a religion at all. There was no structure or dogma of any kind. It was a collection of men and women of all ages from all parts of the world, which was quite an unusual thing in India at that time.

Sundarananda

We were many races, nationalities, creeds and religions, but all were united in a driving quest for an ultimate truth. There was absolute equality and, in a sense, freedom. There were no impositions of what one could do, as long as it was done with the spirit of sincerity.

Sundarananda

In a sense, I participated in life at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram during its golden age, when all the disciples were in close touch with both the Mother and Sri Aurobindo. It was, in a way, an ideal existence on earth, without a trace of rancour or harsh words, arguments, egotism, but with all in concert in search of a divine consciousness.

Sundarananda

There were evenings of great beauty with music and dance, usually held in the quarters of Dilip Kumar Roy, who had a large room and terrace overlooking the Bay of Bengal.

Dilip was an accomplished instrumentalist, and he was often joined by Sahana, who had one of the loveliest voices in all of Bengal. Sahana’s room was on my street, and her voice, raised in devotional songs, would often fill the still, soft air of the evening.

Sundarananda

I had another very dear friend in Mridu, a roly-poly Bengali woman who was Sri Aurobindo’s cook. Often she would call to me in Bengali “Sundarananda-ji, come for some prasad.” The food that she spoke of was that returned to the kitchen by Sri Aurobindo, who ate sparingly: it was blessed by his having touched it.

Sundarananda

My helper Shiguru (Shiva Guru) was a very devoted and useful man. He was so intent on pleasing that when I had my meal brought to my room, he would butter my bread on both sides.

Sundarananda

He was very friendly with the workmen. though my work was more with the concreting machines (the crude-oil engines, winch, hopper and vibrator) and with the steel-framework (bending, laying, and tying the iron rods of different diameters), I was in fairly close contact with him, and so I had a good opportunity to observe and appreciate the neat, meticulous, concentrated, hardworking and cheerful spirit of the typical Japanese character. Gradually I noticed that not only was his work going on outwardly for the construction of the building, but work was going on inwardly in him too, for the construction of himself. The fact that he would not miss the pranam and meditation, that he stopped taking pocket-money for his work, that he took his food in the dining room like all the rest of us, even that Sri Aurobindo gave him a new name, "Sundarananda", by which he came to be known to us thereafter, all speak for his sincere inner work.

Mrityunjoy

The notebook that he kept during his stay was embellished with tiny ink drawings illustrating his way of detailing certain parts and processes for the building of Golconde, all of which had to be approved by the Mother before proceeding. It was certainly a different sort of training than he would have received anywhere else in the world. Indeed, it was a spiritual, as well as an architectural adventure.

Sundarananda

The silence would be intense. In season, the strong, sweet odour of oleander would float into the room. Even this small formality of the evening meditation was not obligatory, and many did not attend.

Sundarananda

The object of the meditation was first to quiet and control the mind, and then, in silence, to aspire to unity with the higher divine forces. I am sure that many achieved this.

Sundarananda

Darshan Days

The weather was always perfect of course. At that time people would come from all over India and the world. Sri Aurobindo and Mother would see all the Ashramites personally one by one. We’d go in by Purani’s room and upstairs and Mother and Sri Aurobindo would be sitting on the couch side by side. We’d go to Mother first. We all had a flower and we laid it on her lap, then put our heads down on her lap and she’d give us her blessing on the back of our head. Then we’d go to Sri Aurobindo and get his blessing. Sri Aurobindo would take so much time that we’d reach a state of ecstasy. I think that was true for everyone. He touched us on the back of the head and that was it. It was the most extraordinary experience. You’d feel a sort of elation going through your body. I don’t think it was just psychological. I think it was actual.

Sundarananda

The daily routine was extremely simple. There was no early morning saying of the offices, no dogma or ritual, no mantras, no ablutions under a waterfall, no counting of beads―only a complete freedom, as long as one's aspirations were sincere. The search for pure illumination took precedence over a spirituality stifling dogma.

Sundarananda

Mother conducted prosperity once a month. At that time we received a dhoti and a bar of soap and 2 rupees for spending money. We received it directly from Mother and that was all we wanted.

Sundarananda

All of our activities are based on the ego and there is no sense of surrender, that Eastern mode of thinking on which Sri Aurobindo has placed so much importance. In a strange way, in the most tiny of places, there is a great light, and we must follow it.

Sundarananda

Since I felt I was receiving more than I was able to give – the answer to all my searches, finally conferring meaning on my life – I refused a salary and joined the community. Sri Aurobindo gave me the name of Sundarananda, which translates from Sanskrit into English as “One who delights in beauty” .

Sundarananda

There wasn’t a bit of rancour. During the whole time I was there I don’t think I heard a harsh word. There was such joy, such beauty. A lot of it was the way Ashramites walked down the streets and how they looked, the depth of their eyes. Pavitra especially had the most beautiful eyes one can think of. They had such depth. And he would look at you straight with such beautiful eyes and it would just overwhelm you. And everybody thought that way.

There was a blacksmith, Manibhai who evidently had been given up for dead when he went to the Ashram. I don’t know how he got to be a blacksmith, but he had become a person of great physical strength. He never walked – he always ran. We asked him why and he said that he thought if he walked, the Mother would think that he wasn’t feeling well. So he’d always run.

Sundarananda

Nishtha (Margaret Wilson) at Casanov with friends Meenakshi, Ansuya, Mona, Doraiswami, Front: Udar, Gauri, Ambu, Nishtha |

Outing with friends Umirchand, , Tulsi, Yogananda, , Harikant, Kanha |

|

Pavitra. Ashram Terrace |

Sundarananda. Ashram Terrace |

About a year after I had come to the Ashram, Margaret Wilson, the 40-year-old daughter of Woodrow Wilson, arrived. Although she was scheduled to stay for only a short visit, she fell more and more under the spell of the sincere environment. Eventually she stayed at the Ashram for the rest of her life. Jyotindra, a young engineer, and I spent many delightful evenings listening to her stories of the White House and her travels with her father in Europe.

She had one of the few refrigerators in the Ashram, so we had the treat of a glass of cold water as we passed the time.

Sundarananda

One cannot construct a highly sophisticated building or run a large-scale Ashram by being inactive, negative or pessimistic. Thus, there is an intensively active side to many aspects of Karma Yoga, the path of action. The Ashram itself carried on various practical activities: a book printing and binding shop, a blacksmith and a machine shop, a bakery and kitchen, a farm and a dairy. In addition, there were unskilled labourers performing the many ordinary tasks necessary to bind a community together.

Sundarananda

When a group of people concentrate with absolute sincerity and devotion on the common objective of a divine life, a creative spirit permeates the group’s whole existence. There is never a harsh word, never an egotistical argument. The group members are beyond pride. Of dualities there are none –no successes or failure, no right or wrong, no just or unjust, not even good or evil. Everything becomes the handmaiden of a deeper search for consciousness; all fades into an awesome light. Movements are slow and measured, smiles heartwarming. There is none of the frenzy of the outside world. Conversations revolve around a simple, unique theme of search for divine union, for all are believers or near-believers.

Sundarananda

After about two years, the time came for me to decide whether to stay on for life at the Ashram or return to the outside world. The way of life in this haven was perhaps as close to heaven on earth as is possible. As with all major questions, the Mother had the final say as to what my future was to be. When I finally decided that I wanted to leave, I asked her for permission. She wrote her answer in the centre of a sheet of paper: “yes” in letters so small that I could barely read them.

Sundarananda

After two idyllic, catalytic years at the Ashram of Sri Aurobindo, the world outside the community still beckoned him, so he reluctantly asked permission to leave. It was 1939 and international tensions were escalating. He returned to Tokyo to work for six months with a former colleague. During his second stay in Japan, he met Marion Okajima, like him, a Japanese- American of samurai background. They were married in Los Angeles on February 14, 1941.

Sundarananda

In accord with Sri Aurobindo’s philosophy, Nakashima believed that the subtle, complex inner worlds of consciousness were more important than the more superficial physical and intellectual worlds: he believed that a deep understanding of that inner world was essential to conquer the tyranny of the ego. Thus he fought against the egotism of modern art by practising Karma Yoga, the yoga of action. Work for him was a spiritual calling, a linking of his strength to a transcendent force. When he established his own studio in Bucks County, he wanted it to be a center for the evolution of a life moved by a higher consciousness, a life of the spirit.

Mira Nakashima

Because Nakashima served as general contractor and on-site architect for Golconde, he acquired a passion for and knowledge of reinforced concrete construction, which he carried with him the rest of his life.

Although his observation of the construction of Le Corbusier’s Pavilion Suisse in Paris served him well, it was the gentle but firm spiritual training of the Ashram that made the greatest difference in his life work.

Sundarananda

Sri Aurobindo’s Action, September 1986 Vol 16, No.9, p.7

Dear Udar

I was very happy in the Ashram and it was a difficult decision to have left, as it was a beauty and life there that could have been an example, and is – to the whole world. I asked permission from the Mother, if I could leave, as I knew that there was an impending war and Japan had already invaded China.

As with all of us, I had no funds and the only income was two rupees a month, as you remember, that all of us received, but she did give me a small funding which enabled me to return home. I went via Calcutta, travelling in third class trains and although I didn’t have plans, Udai singh gave me a letter that I should take to his house. … I became almost a member of the Nahar family and in between I took a short trip to Darjeeling, which I enjoyed very much.

Ultimately, I did get back to Japan, and it was necessary for me to travel through China. It was a very dangerous route for me as a Japanese, and at one point I almost did not make it with an encounter with a group of Chinese. The Mother intercepted and saved my life. I did spend a short time again in Japan and then returned to the United States.

Love from us all,

George Nakashima

Nakashima, a graduate of MIT, was interned together with his wife and children in a desert camp in Utah. … I had to sign a guarantee that he and his family would not become a public liability to the community. Noémi and I undertook this responsibility gladly, knowing well that George was a thoroughly loyal citizen of the United States and should not be subjected to such unbelievable treatment.

Antonin Raymond

It took me nine months, but I succeeded in getting him out of the camp with his wife and children and to our farm, to stay for two years. George started a little workshop in one of our milk houses, to do some small pieces of furniture. After the war, he rented a house not very far from us, where he managed to get a real workshop. Still later, he acquired some property in our neighbourhood and constructed his present house and studios. He is now one of the most prominent Japanese craftsmen and architects in the United States, well known and highly respected.

Antonin Raymond

His life was interrupted by World War II and which led to the internment of Americans of Japanese descent. Life in camp was hard on everyone, but Nakashima asserted later that the wounds left by that experience “healed over and left no scars”. Its bitterness was mollified by the generosity of the Quakers and eventually led to the conception of the globe-encircling Altars for Peace, so that all peoples might some day be able to work out their differences in a peaceful manner.

Sundarananda

At any given time, the Nakashima Workshop employs a dozen or so workers, including family members. Nakashima’s daughter, Mira, who received degrees in architecture form Harvard University and Waseda University in Tokyo, worked as his assistant designer for 20 years and took over the task of producing backlogged orders after his death in 1990. Since then, as head of the Nakashima Studio, she has experimented with new forms, collaborating with other architects and developing new work such as the “Keisho” group.

Mira Nakashima

Believing in the integration of a personal and professional life, Nakashima began his business as a one-man shop and continued to operate on this principle throughout his career. He developed an international reputation and received many important commissions for buildings and furnishings for churches, corporate headquarters and private homes. A master craftsman, he created a distinctive style of furniture that gave “a second life” to the trees he loved so much. Nakashima received numerous awards, including the Gold Craftsmanship Medal of the American Institute of Architects, 1952.

Mira Nakashima

The world without spirit is predominantly pragmatic and materialistic. The two elements of politics and economy, capitalism and communism, lead us to a ‘gut-feeling’ that they are both wrong, and wrong in an extremely tragic way.

Sundarananda

One can only think in terms of the Mother’s soft, sweet and strong way of solving problems in the Ashram, in relation to the whole world around us.

Sundarananda

Sri Aurobindo’s thought was to become one of the most powerful influences in Nakashima’s life. in fact, he considered himself a disciple of Sri Aurobindo to the end of his days. During his stay at the Ashram, Nakashima gave up his salary from Raymond’s firm and became a member of the community, probably intending to spend his life there.

Sundarananda

Our work here has been to love nature and its trees, to search for beauty in them, and to give them a “second life” as eternal as possible. It is a spirit of my people, the Japanese. I have tried to live up to “Sundarananda” the name given me by Sri Aurobindo.

Sundarananda